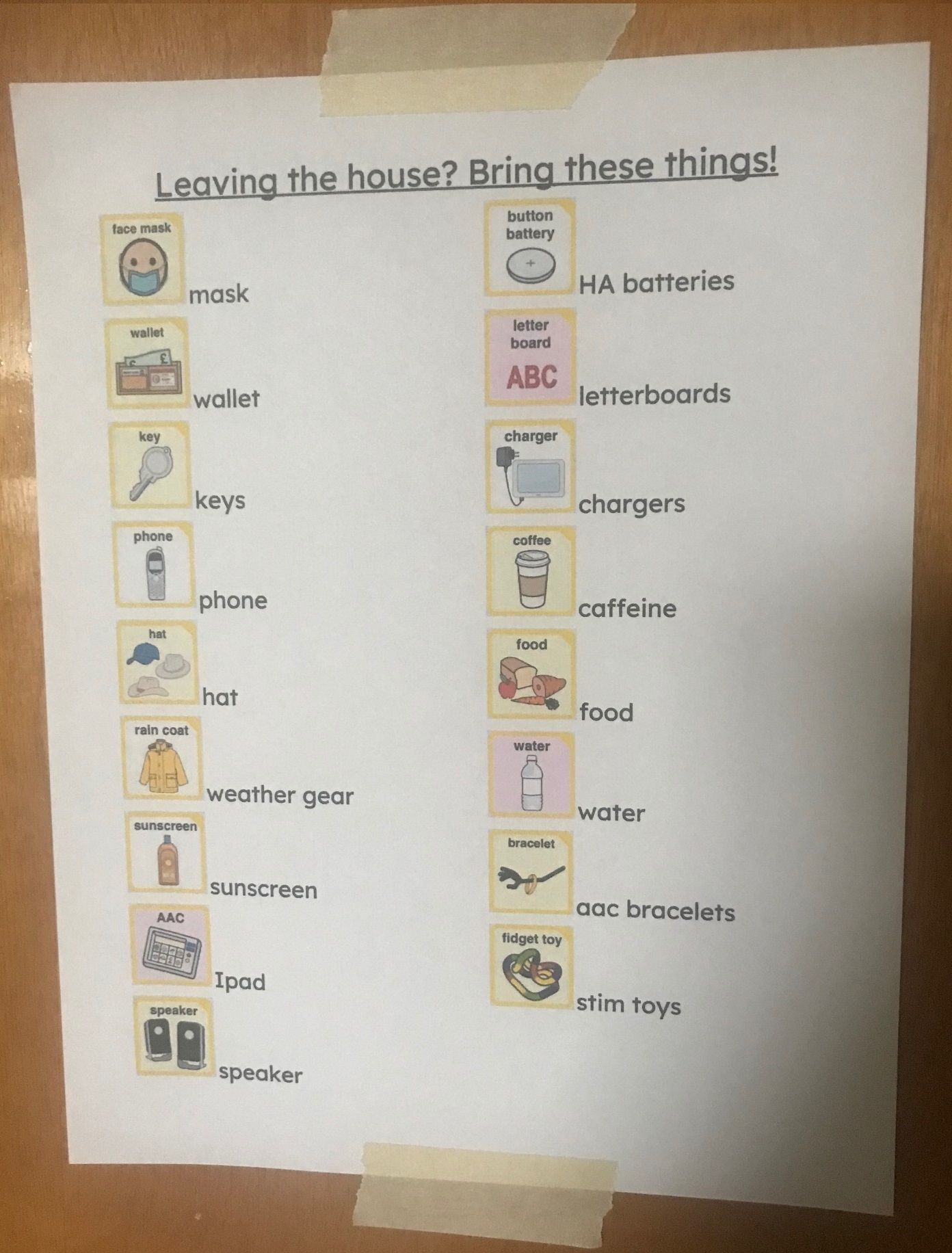

I gave a presentation at AAC in the Cloud this week about creating backup AAC methods for when your primary method isn’t a good option. I wanted to turn a couple parts of this presentation into blog posts, and this will be the first one – a list of ideas for wearable and other highly portable AAC (that you could use as a backup or as your primary method). If you’re more of a video/slideshow person feel free to watch the presentation linked above instead (there’s a transcript of my speech in the notes section of the slideshow if you need that to follow along), but if you’re more of a reading-a-blog person this is for you!

Please note that I’m not trying to advertise any specific brands in the links provided below, I just want you to be able to see examples of the possibilities that are out there. If you’re considering purchasing something to use as wearable/portable AAC, do your research in order to choose between the sellers available. If you’re considering crafting something to use as wearable/portable AAC, do your research to see how others have created similar items.

First of all, for partner assisted scanning, you don’t need any physical objects at all, just another person who can provide options auditorily or in sign language. This is a great method of communication for people who are having a really hard time with motor control or physical fatigue, because you can use as little as one small muscle movement to indicate a positive response when your communication partner says the option you want to select. I have friends who frequently use their head or eye gaze to select options when their devices are broken – their support staff might say two options, holding up a fist for each in opposite locations, and the AAC user can turn their heads or eyes towards the one they want to select. Another acquaintance of mine can stick out their tongue slightly to select an option or indicate “yes”. With a skilled communication partner these methods can lead to a huge range of self expression, and if you’re a support person for an AAC user I encourage you to learn as much as you can about how you can support robust communication using partner assisted scanning.

Another AAC method that’s completely portable because it doesn’t require any physical objects is expressive sign language, modified signs, or home signs. I don’t recommend using signed English or other gestural systems that are based on spoken grammar, because learning even a little bit of an actual sign language like ASL, including exposure to Deaf cultural norms, will lead to greater potential for connections with sign language communities across the lifespan. It also provides a better chance of access to interpreters who will understand you accurately as a communication support – for example, I often use interpreters for medical appointments. ASL or whatever your local sign language is can be a great backup AAC method. If you have motor skills impairments you might be able to learn modified signs that fit your abilities, and there are still interpreters who are skilled at understanding those. For AAC users who are certain they really only want to be able to communicate with their immediate family or caregivers, home signs or idiosyncratic gestures are another option for a backup method. Sometimes nonspeaking people will develop these kind of home signs independently, so if you notice someone you know using the same gesture over and over, try to figure out what it means! It’s entirely possible it’s a stim, but it could be communicative.

Those are the nontangible forms of AAC that are probably the most portable of all methods, but there are almost endless objects you can use as wearable communication supports too. Note that a lot of these can also be used for partner assisted scanning with aided visual input, where your support person points to each option as they list it and wait for you to select the one you want. For example a few months ago when both me and my friend’s devices weren’t available, I used a letterboard both to direct select what I wanted to say where my friend could see it and to use my finger to indicate each letter for them to select the ones that spelled out their messages. It was slow, but it was honestly lovely to be able to have a direct conversation together without needing fancy tech or speaking people to intervene!

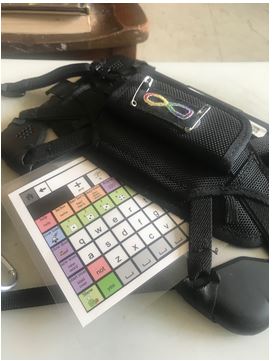

Perhaps the most obvious way to wear AAC is to put your communication device on a strap or wheelchair mount! If you use a tablet like me and its case doesn’t feature a built-in handle, I recommend Otterbox’s harness and strap. I typically sling this over my shoulder when on the go so that my device is always nearby.

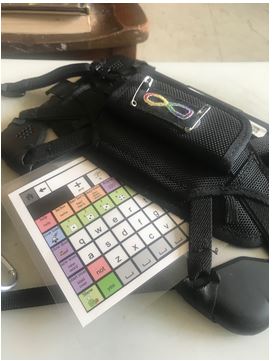

Additionally, if you almost always have your device on you but want to prepare for when it runs out of batteries, you can keep a small letterboard taped to the back of it or tuck one into its holster. Here is a link to a simple letterboard I designed that you’d just need to shrink or expand to your ideal size before printing. I definitely recommend laminating the printout so that it holds up over time – well, I recommend laminating pretty much everything. Small laminated letterboards are also easy to tuck into a purse or backpack.

(Image description: a small laminated letterboard with some core words and symbols peeks out from the holster of a tablet. The holster has a small neurodiversity symbol patch safety pinned to its handle.)

If you like to handwrite you can wear a miniature notebook and pen, or whiteboard and pen, around your neck or clipped to your shirt or belt. This can be homemade with dollar store materials or a pre-made set purchased online like this small whiteboard designed for nurses.

(Image description: a small green spiral notebook with a faint drawing of the Harry Potter “Deathly Hallows” symbol hangs from a loop of yarn, with pen attached with another small loop and tape.)

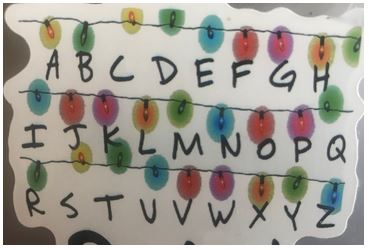

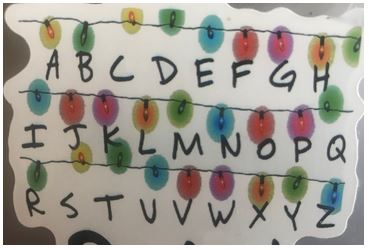

Even if your typical style isn’t exactly spooky, an Ouija board shirt or pillow conveniently doubles as a letterboard. Or this is even more niche, but if you’re a fan of the Netflix series Stranger Things, look for merchandise that displays Joyce’s string lights alphabet wall.

(Image description: A close up shot of a sticker with three rows of string lights, each letter of the alphabet scrawled underneath.)

You can attach a luggage tag that is printed with letters or important symbols to a keychain or lanyard. Sometimes there are luggage tags like this pre-made online, or you can print your own designs at home and seal them onto both sides of an old gift card with a sturdy glue or tape, punching a hole for the attachment – here is one I made. I recommend taping over the entire card with packing tape before punching the hole in order to provide a sort of homemade waterproofing. You can fit more than one of these on a single lanyard or keychain if you want to increase the vocabulary you can fit on it.

(Image description: a rounded rectangle card attached to a lanyard with metal clasp features words and symbols for yes, no, stop, go, help, and bathroom.)

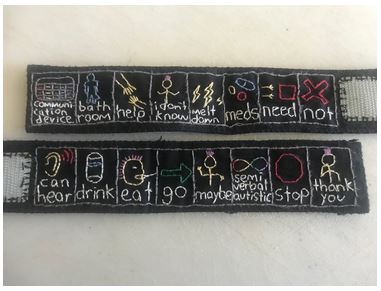

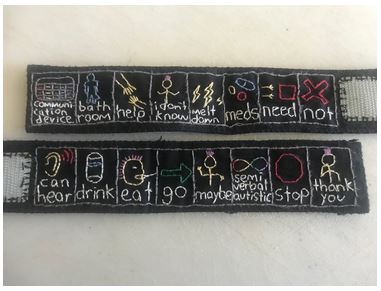

Some companies custom print snap bracelets, or if you’re a seamstress you can hand embroider a fabric bracelet with symbols and words for a wearable and washable option. I have made several of these for myself and friends, and they’re really handy especially for quick interactions! You’re welcome to message me on Etsy if you’re interested in purchasing one from me. Another option for a homemade bracelet is to attach a small laminated symbols board to the cuff of an old sock.

(Image description: Two embroidered bracelets with velcro closure feature words and symbols for communication device, bathroom, help, I don’t know, meltdown, meds, need, not, can hear, drink, eat, go, maybe, semiverbal autistic, stop, and thank you.)

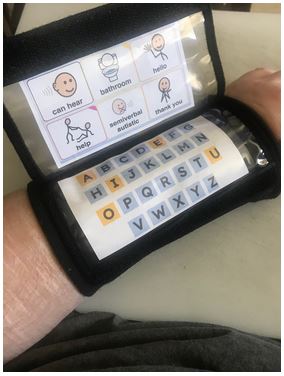

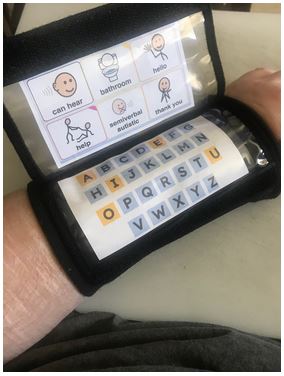

Football playbook wrist cuffs offer plastic sleeves you can insert your own letterboard or symbols board into:Here’s a picture of mine. It’s not perfectly waterproof but holds up decently as it’s designed for outdoor use.

(Image description: a wrist cuff with plastic sleeve worn on a white-skinned scarred arm unfolds to show a letterboard and a small symbols board with the words can hear, bathroom, hello, help, semiverbal autistic, and thank you.)

If you’re someone that always has your phone in your pocket or on a belt holster, a free or low cost app like Speech Assistant could be handier for a quick conversation than getting out a bigger device. My phone doesn’t have great volume but I frequently hold it out for a communication partner to read in circumstances like running errands or talking to neighbors.

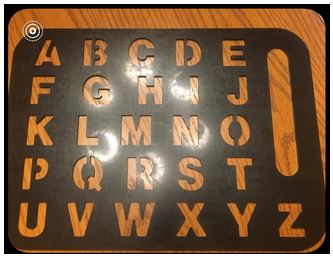

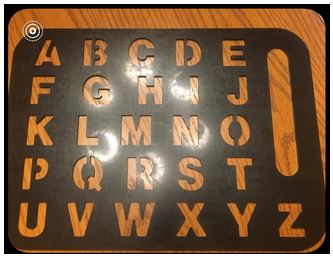

A sturdy plastic alphabet stencil or letterboard can be attached to your backpack with a carabiner, here’s an example of my friend’s.

(Image description: a grey alphabet stencil with large capital letters and handle resting flat on a wooden surface.)

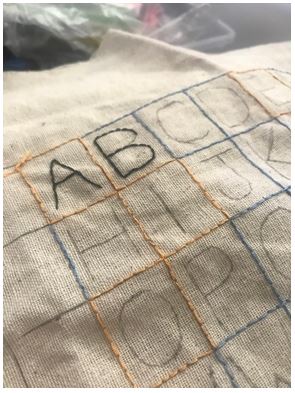

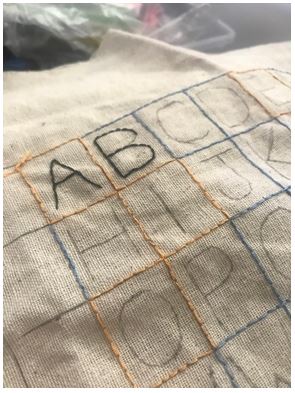

There are companies that custom print bandanas you could design with symbols or words tailored to your communication needs: I haven’t tried this but I’m working on embroidering a letterboard that will be similarly foldable, washable, and hardy.

(Image description: a grid of embroidered rectangles on rough fabric with a letter faintly drawn into each, so far only A and B have been filled in with stitches)

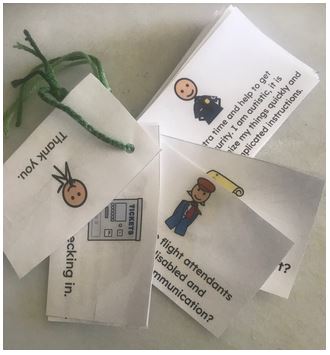

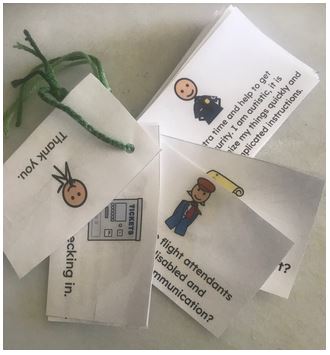

You can buy pre-made sets of communication cards on keyrings, but I recommend printing and laminating your own in order to choose vocabulary that is going to be most useful to you. This picture is one I made for when I travel, it’s useful to have something with me while my Ipad has to go through the X-Ray machine, in case I need to say anything to TSA agents. Again, I laminated with packing tape as a cheap alternative to paying for lamination at an office supplies store.

(Image description: a stack of small cards hanging on a loop of yarn. Four cards are splayed out with symbols on each, and text only partially visible: 1) a person touching their mouth with text reading “thank you”, 2) a ticket machine with text reading “…checking in”, 3) a flight attendant with text reading “flight attendants… disabled and… communication”?, and 4) a security guard with text reading “extra time and help to get… security. I am autistic, it is… organize my things quickly and… complicated instructions.”)

For blind and low vision AAC users, one wearable option I saw online is a belt with Braille cards for different words. For folks not fluent in Braille, you could use raised line drawings. This would be great for AAC users who primarily use a tactile based communication device but temporarily don’t have access to it.

Alphabet beads can be strung between spacer beads in order to make a necklace that’s right there for you when your letterboard isn’t handy: This would be best for folks who have good fine motor skills.

(Image description: beads with letters on them strung alphabetically between rainbow-ordered star shaped beads)

A medical alert bracelet is another form of AAC! Holding it out to somebody and pointing is a way to disclose that you are nonspeaking, which can be helpful in emergencies or even in everyday situations where someone doesn’t understand why you’re not responding to them as expected. I also use mine to refer emergency medical staff to the full info sheet I keep in my wallet.

(Image description: A medical alert bracelet on a white-skinned wrist reads “autistic, semiverbal, needs Ipad to communicate fully. Complete medical info in wallet.”)

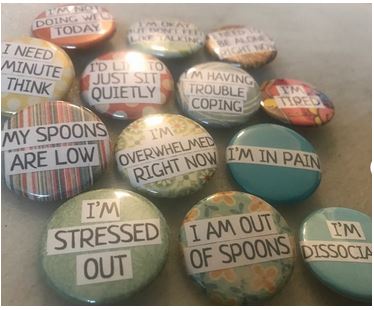

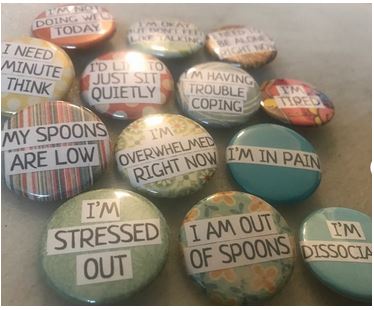

Status badges can communicate all sorts of things about your present state of mind. You could choose a certain one to wear on your shirt until it’s no longer needed, or keep a set pinned to keychain webbing or a foldable piece of fabric with you at all times so that you can point to relevant ones as needed. One option is using the red, yellow, and green communication badge system that the Autistic Self-Advocacy Network recommends, but you can also purchase or make more specific messages indicating to people around you what you’re coping with or what you need. Here are some I’ve made.

(Image description: Colorful round pinback buttons read: I’m stressed out, I am out of spoons, I’m dissociating, my spoons are low, I’m overwhelmed right now, I’m in pain, I need a minute to think, I’d like to just sit quietly, I’m having trouble coping, I’m tired, I’m not doing well today, I’m okay but don’t feel like talking, I need to be alone right now.)

Other buttons and pins are forms of communication too! One example common in queer circles is pronoun pins that tell people around you what gender pronouns you go by. I wear these on my backpack and hat so that I don’t constantly have to find the right folder in my device to tell people they’re referring to me incorrectly. These are also available on my Etsy if they’d be helpful to you.

(Image description: colorful round pinback buttons feature sets of neopronouns – ze/hir/hirs, ve/ver/vis, fae/faer/faers, co/co/cos, xe/xem/xyr, zie/zir/zirs, and ey/eir/eirs.)

Okay, those are my ideas for wearable/portable AAC methods! I almost always have more than one with me as backups for when my device isn’t the best option. Do you wear your AAC everywhere too? What do you use? Feel free to comment below!